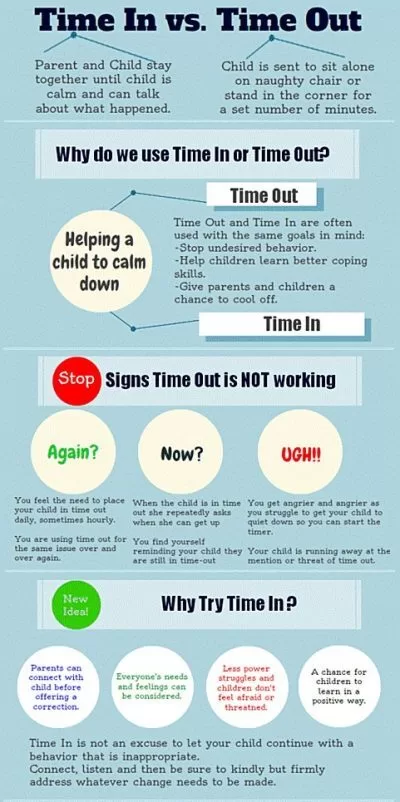

TIME IN vs TIME OUT

REPAIRING RELATIONSHIPS WITH A TIME-IN

(This is a guideline. It is, of course, harder than this page makes it sound.)

I’m Upset and My Child is Upset

When necessary, I start with a “Time-Out”* (for me, for my child,

or for both of us) until:

I know that I am bigger, stronger, wiser, and kind, and

I remind myself that no matter how I feel, my child needs me.

(* A “Time-Out” can be helpful as a first step, but not as a punishment.)

- I’m Calm (enough) and My Child is Upset

We can build a safe “repair routine” together (remember: the first 1,000 times are the hardest!).

I take charge so my child is not too out of control. We can change location.

Go to a neutral place that is our “Time-in” spot, where we sit together and let feelings begin to change.

I maintain a calm tone of voice (firm, reassuring, and kind).

We can do something different (for several minutes): read,

or look out the window, or attend to a chore together.

I help my child bring words to her/his feelings.

(“It looks like this is hard for you.” “Are you mad/sad/afraid?” )

I talk about my feelings about what just happened.

(“When you did that, I felt…”)

( Rule of thumb: Stay in charge and stay sympathetic.)

I’m Calm (enough) and My Child is Calm (enough)

I use the following to support our repair and to make repair easier in the future.

I help my child use words for the needs and feelings that s/he is struggling with

by listening and talking together. (Remember KISS—

Keep It Short And Sweet)

I help my child take responsibility for her/his part and

I can take responsibility for my part.

(Rule of thumb: No blaming allowed.)

We talk about new ways of dealing with the problem in the future.

(Even for very young children, talking out loud about new options will establish a pattern and a feeling that can repeated through the years.)