WHAT IMPACT HAS THERE BEEN ON YOUR FAMILY HAVING YOUR ADHD CHILD

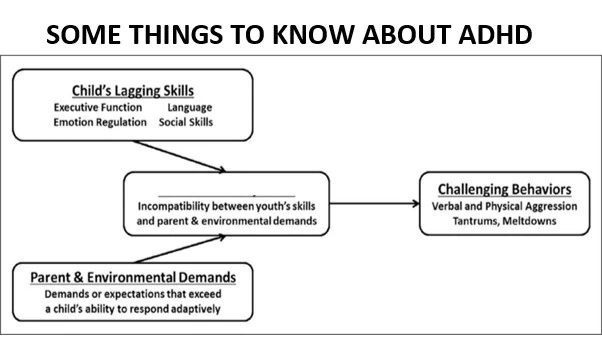

Many children who struggle with behavioral challenges don’t have the skills they need to do what’s expected of them, and unfortunately, ADHD behaviors can lead to harsh — and mistaken — assumptions. The conversation about ADHD and executive function skills most often focuses on academic skills. What’s missing, however, is recognition of how executive function affects social behavior. Social challenges are often traced back to underlying ADHD.

Executive function is the brain’s hub of skills — memory, organization, planning, self-regulation, and the ability to modify our behavior in response to others.

Many tend to live in strong emotions, meaning that the feel emotions much stronger than your average person.

- They often seek to evoke strong emotions in their parents

- Some need more attention than other kids.

- Tolerating boredom is extremely challenging, particularly for younger kids when there is not enough structure. This often leads to negative behaviors

While they would prefer positive attention from family members, they often seek out negative attention as it doesn’t feel vulnerable.

They also learn it’s easier to get negative attention.

Negative attention often evokes strong emotions in family members and gets their undivided attention.

Having emotional reactivity from a family member is a form of attention/connection.

They have difficulty recalling the emotions from past experiences to the present, unless there were strong emotions involved. As a result, we have to help them connect the emotions from past experiences to the present (or near future). This is called episodic memory.

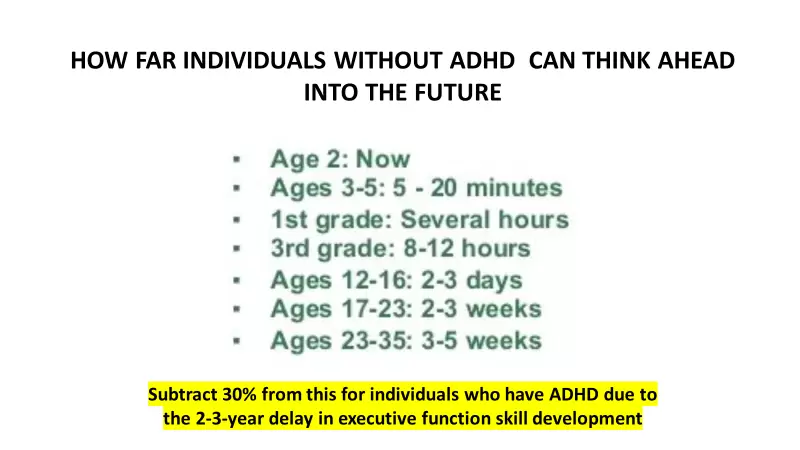

- Their ability to visualize the future is based on their age and approximately 2-3 years behind their same-age peers. This is called non-verbal working memory or “future thinking skills”.

- They learn best in the moment, when there is a relevant context for what you are trying to teach them. This is why parents have the most important role in cultivating positive behaviors, and why traditional “talk therapy” is ineffective at addressing ADHD-related challenges.

They do best with an authoritative parenting approach that uses language in a way that works for the ADHD brain.

- They are often most successful when they feel they have a sense of purpose (are being useful/helpful).

- The respond incredibly well to purposeful praise and recognition. There is a term for this: “Recognition Responsive Euphoria

Many individuals with ADHD learn visually which is why they need visual images of themselves doing the task in order to move from prompt-dependence towards independence.

Kids with ADHD are lagging in the development of their self-directed talk or an internal dialogue (what I refer to as their “Brain Coach”). We need to help them develop their “inner voice”.

- When implemented with consistency, the way you use language with your child can significantly help him to develop his inner voice (self-directed talk).

- You need to model your internal dialogue around your son by verbalizing your thoughts in order to model what your self directed talk sounds like. (E.G.

Work though a problem out loud

- I have to pick up James from karate and need to pick up something for dinner. I guess I can drop him off, pick up dinner and then go back to karate” or

- Tomorrow morning we need to leave by 8 so you will need to look like we’re ready to go at 7:45. I’m going to start dinner first, then I’ll help you with math while dinner is in the oven.” .)

You cannot help your son/daughter improve his/her self-directed talk if you do not change the way you use language with him/her.

Using imaginative communication will help your son see the “bigger picture” and use his own self-directed talk

- Instead of: Pick up your shirt and shorts from the floor and put them in the hamper try:

“Can you please make the floor look like it’s supposed to look.” “Picture in your head out what needs to happen in here.”

Kids with ADHD have episodic memory however their ability to recall past experiences is very much based in strong emotions. If an experience doesn’t have a strong emotion associated with it, they are less likely to remember things from the past in order to use past information for the present or near future.

Super Important!

- If your son becomes frustrated and says, “Just tell me what to do!” do not give in to his frustration and prompt him. Instead, be a little more descriptive with the language you use but do not tell him what to do/directly prompt him.

- Here’s an example of what using more descriptive language could look like. As an example, if he doesn’t see his water bottle on the counter that needs to go into his bag say: “I’m wondering if you might get thirsty later today?”

If-Then Thinking and episodic memory

- If-Then thinking helps to create that bridge between past experiences, the present and the future. E.g. “When you had a book report a few months ago you waited until the night before to do it. You got mad at yourself because you had to do so much work the night before. If you do that again with this book report then what do you think you’ll feel on Thursday night considering it’s due on Friday? If you’re getting ready to go to karate, then what should you be doing right now? What do you do every week about 15 minutes before we leave for karate?

Use visual language as much as possible in order to improve future thinking skills

Using visual language will help your son develop a “future picture” in his head of things coming or what something will look like when it’s completed.

- “We’re leaving for the pool in 10 minutes. Picture what you’re supposed to look like when you’re about to leave for the pool.”

- Imagine in your head what you’re supposed to look like if you lose the game today. What you should look like is your teammates who are in line to shake hands with the other team

The more you use the strategies the more you will help your son or daughter improve his/her self-directed talk (Brain Coach) as well as future thinking skills (non-verbal working memory). • Use imaginative, visual language instead of prompting.

- Share your inner dialogue out loud as much as you can to help your son develop his. If he asks why you’re talking to yourself, explain this to him.

- Considering options and possibilities out loud models what flexible thinking sounds like. Improve episodic memory by connecting past experiences/emotions with things in the present and helping your son see how this past information/emotions are relevant to the current scenario

- If-Then thinking helps to improve episodic memory by associating past experiences with the present or future. Use If-Then thinking when you anticipate your child is not recalling what happened in a similar scenario or needs help remembering how the felt in a similar, past experience.

- Significantly reduce the amount of direct prompting you do. If you do not do this, do not expect results.

- You can use visual language to help teach situational awareness (read the field).

Difficulty with non-verbal working memory (future thinking skills) make it difficult to visualize how you’ll feel when an undesirable task is completed and what the end result should look like.

- May think an undesirable task will take longer than it will due to their difficulties with conceptualizing time

- Difficulty with recalling past information and applying it to the present such as how he/she was successful getting through a undesirable task in the past.

- Expecting him/her to transition from preferred to undesirable without helping him/her prepare for the transition.

- Manipulation of parents through learned helplessness, tantrums/meltdowns, arguing, self-defeating comments.

In order to be motivated we need to be able to visualize how we’ll feel when we complete a task.

- Motivation is what directs our actions towards a goal.

- If you have ADHD, your future thinking skills are lagging thus it’s difficult for you to visualize the future.

- Lack of motivation is not laziness.

Lack of motivation does not mean unwilling; it means you can’t picture how you’ll feel when a task is completed.

- If your want your son/daughter to be motivated, he/she will need practice with learning how to conceptualize feeling good about completing an undesirable task, visualizing what the end goal should look like and being able to conceptualize how long the task will take.

- Star charts, checklists, earning things several days later, etc. typically don’t work as incentives for kids with ADHD. The time frame for the reward/incentive is too far into the future, out of the “time horizon” thus it feels abstract to them.

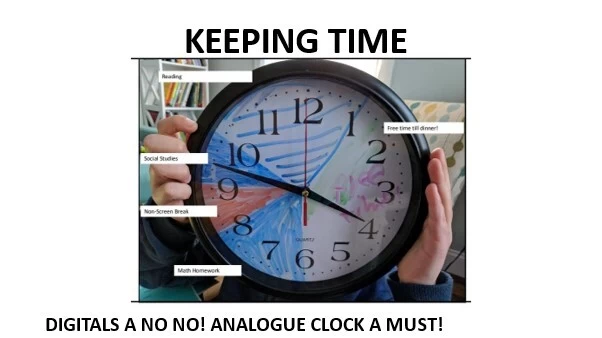

Kids with ADHD lose track of time when they are doing a preferred task, especially ones in which they may hyperfocus.

- They often think undesirable tasks will take longer than it actually will.

- The way to sell this strategy is to explain that by using the clock it will help him/her learn how to use their time more effectively which will then give him/her more free time.

Remember: Your son/daughter should be coloring in the clock, not you. This helps to develop spatial awareness of time.

- You can help your son/daughter guesstimate how long each subject will take before coloring in the clock.

- Make sure to include breaks in the coloring if necessary (color the breaks in a different color)

- Make sure homework order is from (most frustrating/difficult to get through to easiest)

The more your son or daughter can see analog clocks the more it will help them learn how to conceptualize time.

Remember: You want to use indirect language to help him/her develop his/her self-directed talk:

- “Where are you on the clock right now”?

- “It looks like the big hand moved out of the (break color)”

If you see your son/daughter getting distracted/off-task use language like this:

- “Is something you’re doing right now taking away your free time?”

- “Were you planning on cutting into your free time this afternoon ?”

- By using this language we are helping to build self-directed talk (Brain Coach)

Using the clock to get off video games (Or transition from any preferred task to a undesirable task)

- This only works for time up to an hour

- Future plan time is part of his time, however it is when he needs to start visualizing what’s coming up next (in preparation for the transition)

- .Future plan time is the last 5 minutes before his time is up and is colored in a different color than the rest of the time

- .We need to use visual language when talking about future plan time.

- The goal here is not to do any prompting around future plan time eventually.

The way kids can learn how to “feel” time is through seeing time physically move through unit volume.

This is why we use an analog clock. Analog Clock=Physical movement/Coloring in time frame=unit volume

- I recommend having two clocks/packs of markers around the house, so the clock doesn’t need to be carried around.

- You can use small post-it notes to stick on the clock so show what the color represents.

- Best to use the same color markers for same things – Example: Red marker=break, blue marker=schoolwork, green marker=chore

- “Sell” your child on using the clock by explaining to them it absolutely will give them more free time to themselves because it’s helping them learn how to see how they’re using and wasting time.

- The clock needs to be next to the TV/monitor so your son can it while he’s playing.

- Future plan time needs to be a different color than screen time.

- Your job is not to remind him that his time is almost up. You can remind him that “future plan time” is approaching.

- Do not say “5-minute warning” instead say future plan time. The word “warning” does nothelp to prepare for a transition or visualize the future.

- You can set up a contract in advance of using the clock where going past future plan time means however long he’s not doing what he’s supposed to be doing is how long he’s taking off of his screen time the next day.

- If your son goes over his time use language to put the responsibility on him: Example: “I see you chose not to get off at the end of future plan time. I guess you’re choosing to take some of your screen time away tomorrow?”

UNDESIRABLE TASKS

Your job to help your son or daughter develop the ability to persevere through undesirable tasks involves a few variables:

- Prioritize what is most important, I suggest whatever task causes the most stress/arguing in your house.

- You need to help your son learn how to experience motivation through using visual language to help him visualize what he will feel like when the undesirable task is completed.

- Most importantly, you need to provide a lot of praise and recognition for getting through undesirable tasks and helping him connect past successes with getting through tasks in past.

- Remember: Praise effort and resiliency not intelligence!

The key components to helping kids get through undesirable tasks:

- Incentives/rewards that are within a reasonable time horizon, consistent with their ability to visualize the future. As immediate as possible is best.

- Using visual language to help picture what he’ll feel like when the task is done.

- Recalling past successes with getting through undesirable tasks and illustrating how it’s connected to the present.

- Extremely Important: Praise and recognition for getting through undesirable tasks is an absolute necessity.

Make a list and ask yourself these questions:

- What undesirable task do we argue about the most or which causes the most tension in our house?

- What skills/routines can my son be doing on his own right now that he’s not doing?

- If I were to rank the 3 most important tasks/skills, he needs to learn to get through without my prompting/supervision what would they be?

Visual language to help improve motivation

“Picture in your head last time you had to do this, it took you 10 minutes and you did a great job. It should not take you any longer this time. You can color in the clock to show you that it won’t take more than 10 minutes.” “Imagine how good you’ll feel when this is done and then you have free time until dinner.”

“Why should he be praised for doing something everyone else has to do? We don’t praise or other kids for this.”

- Because ADHD is “Intention Deficit Disorder” You may intend to accomplish something, but you can’t sustain attention on it for long enough to complete the task (if it’s undesirable).

- Frustration tolerance/resiliency are cultivated, and it can take much longer for kids with ADHD to cultivate this skill.

- Punishment, consequences do not teach resiliency to persevere through undesirable tasks.

- Praise and recognition are more effective than yelling, punishments, lectures, etc.

Mistakes parents often make in the process of helping their child learn how to get through undesirable tasks

- Getting sucked into the “argument rabbit hole”: Arguing about why a task needs to be done, trying to justify why they need to do something, getting off topic because your child changes the topic, making threats of punishments, etc.

- Doing the task for their child because they get tired of asking.

- Assuming their child will be able to conceptualize how long the task will take.

- Not giving a clear time frame in which the task needs to be completed.

- Feeding into manipulation by learned helplessness and self-defeating comments.

Getting through undesirable tasks must be incentivized with small, immediate “rewards” that happen as soon as possible to the task being completed.

- You need to do some brainstorming with your son or daughter so you can agree on what those rewards will be.

- For kids who have trouble getting off screens I do not suggest short amounts of video game time as that can lead to bigger problems.

- Very important: the younger he/she is, the more immediate the incentive needs to be.

Here’s what does not work:

“If you get done all your homework this morning you can have extra computer time this weekend.”

Getting through undesirable tasks must be incentivsed with small “rewards” that happen as soon as possible to the task being completed.

Here’s the language you use incentivise getting through undesirable tasks:

- “If you choose to complete your chores the way I expect them to be completed then you can choose to have 30 minutes of YouTube or Minecraft time.

- “If you’re able to complete everything you need to do this morning and look like you’re ready for school by 7:00 then you can watch TV for 20 minutes. Getting on Xbox or the computer is not a choice for that time period. If you don’t want to watch TV you can suggest something else that’s not Xbox or the computer.”

- How I sell this to kids: More free time to yourself to do what you want if you spend less time arguing/complaining and get the task done.

Here are some examples of small, tangible rewards

- “If you complete your morning routine by 8:15 you can have tablet time for 15 minutes.” (Refer to webinar 2 to learn how to get through daily routines)

- “After you brush your teeth and get ready for bed, we can play 1 game of checkers.”

- “When you finish math homework you can watch 2 videos on YouTube for 10 minutes before you start reading. When you finish reading you can watch 15 minutes of videos.” (The incentive increases with more homework completed).

- “You can have your phone early if you can finish your chores within 10 minutes.”

Here’s how you motivate your child to get through undesirable tasks

- Do frontloading that includes a time frame so they can conceptualize how long the nonpreferred task(s) will take.

“Today we need to atonement the basement. If you fully cooperate with me it will take 30 minutes. Here’s what 30 minutes looks like”.

- Use visual language to help them visualize feeling good about getting the task done and look forward to the incentive.

“Picture finishing helping me clean the basement and then having free time until dinner.

What do you see yourself doing during that time?”

- Remind them of past experiences when they were successful getting through a similar undesirable task in order to be encouraging

“You did such a great job with helping to clean the garage and if you remember it did not take as long as you thought it would. Can you please show me the same level of cooperation today so you can have all of your free time?”

- Use the clock to help show what time looks like.

Here’s language you can use with the clock

- “It’s 8:15 now, unloading/loading the dishwasher will take no longer than 8 minutes. Here’s what 8 minutes looks like” (Color it in on clock or have your child color in 8 minutes.)

- “You need to start between now and 8:20 if you want to (insert incentive here)”.

[For kids who try to avoid tasks by arguing or are oppositional]

- “If you choose not to do your job then you choose not to have your YouTube time. You’re in control of getting your YouTube time or not.”

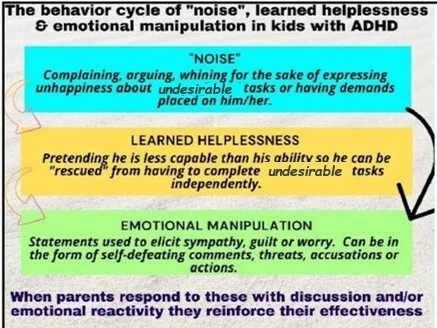

The behavior challenges that cause the most stress at home for families of kids with ADHD is due to parents responding to “noise”, learned helplessness, and emotional manipulation with undivided attention and emotional reactivity. Complaining, arguing, etc. about having to do a undesirable task. Being relentless about trying to start an argument, justify why he should get what he wants.

- NOISE is often a form of “venting”, which is fine, and it doesn’t need to be responded to with attention. (We all need to vent sometimes.)

- Noise can be saying “No, that’s stupid.” or “No, I’m not doing that.” to anything new or unfamiliar.

- Kids with ADHD are highly skilled at making “noise” and getting their parents to respond to the noise. This often leads to parents getting pulled into the argument/negotiation/reasoning rabbit hole.

- Noise can be *anxiety. Kids with ADHD learn early on that making noise, is a way to get attention/engagement from parents. Responding to noise can cause emotional escalation. Responding to noise, is guaranteed to cause noise to continue.

WHAT TO DO – DO NOT RESPOND TO “NOISE” WITH ATTENTION/EMOTIONAL REACTIVITY

- Ask yourself this: Am I consistently responding to his noise, and does it prolong the noise making? Am I getting pulled into the argument/negotiation/reasoning rabbit hole?

- Keep in mind that noise is “venting”, and venting is O.K. if it’s done with emotional regulation (not yelling, screaming, getting physical, etc.)

- Remember, not responding does not mean “ignoring”, rather it means you’re not engaging in a discussion or giving emotional reactivity to noise.

Ask yourself this: Am I consistently responding to his noise, and does it prolong the noise making? Am I getting pulled into the argument/negotiation/reasoning rabbit hole?

- Keep in mind that noise is “venting”, and venting is O.K. if it’s done with emotional regulation (not yelling, screaming, getting physical, etc.)

- Remember, not responding does not mean “ignoring”, rather it means you’re not engaging in a discussion or giving emotional reactivity to noise.

LEARNED HELPLESSNESS

- Acting passive or helpless in order to have something done for you or to avoid having to do something independently.

- Feeding into learned helplessness, encourages prompt-dependence.

- Many kids with ADHD combine learned helplessness with self-defeating comments in order to emotionally manipulate their parents. This is not something done to be deceptive, it’s done to avoid doing undesirable tasks independently.

“I don’t know how to fold my shirt and you don’t care. That shows you don’t care about me!”

Learned helplessness can look like this

Not completing a task because he knows you’ll take over and do it for him.

Acting passive until you are doing the task with him (“hand holding”).

Making self-defeating comments to avoid having to do undesirable tasks.

Acting like he can’t do something/Saying “I don’t know how”.

A way to get you to do something for him that he can do himself

The way kids build confidence in their abilities is through recognizing what they can accomplish. It’s fine to start with scaffolding, use the “release of responsibility” scaffolding to help get them started. Confidence does not develop from constant “empty reassurance and praise”, it develops through recognizing your own abilities.

Because of their difficulty with episodic memory, we must refer back to past experiences that they were successful with in order to help them understand they can be successful with the current task.

The language used with this is same but different. An example – “Last time you had to figure out how to find the answers to your science questions you looked through the book, starting at the beginning of the chapter. You found the answers quickly and you felt good that it did not take as long as you thought. This is the same but different, just with social studies instead of science. It is important we attach a positive emotion to the memory to help build that connection of past success.

Some figure out that “learned helplessness” works to avoid undesirable tasks and/or have things done for them, that they can do themselves.

- Some become highly skilled at emotionally manipulating their parents. The most common way this is accomplished is through making self defeating comments.

- Inflexibility often increases around age 14-15 if it has been consistently accommodated.

- Some parents try to “fix” things when their child is upset/frustrated. This often prevents kids from developing self-advocacy and independent problem-solving skills

EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION

Kids with ADHD are highly skilled at emotional manipulation of their parents.

- Often occurs as a way of exerting a sense of control, when limits are held.

- Is a highly effective way to get parents to feed into learned helplessness.

- Used to avoid undesirable tasks.

- Used to get what they want through guilt or worry. Is often most effective on mothers.

Emotional Manipulation is not ADHD specific, yet kids with ADHD can be highly skilled at activating their parents’ sympathy, guilt, insecurities around parenting.

As kids get older, emotional manipulation becomes more sophisticated, here’s an example of what it can sound like in older kids:

“You not letting me on Xbox is keeping me from talking to my friends, I guess you don’t care if I have friends or not.”

It’s very common for kids with ADHD to resort to emotional manipulation when noise and/or learned helplessness isn’t working for them.

They learn early on this is an effective strategy to elicit sympathy from parents, get parents to “give in”, or do what they want.

- “Noise”, learned helplessness and emotional manipulation are common in kids with ADHD, who are highly skilled at figuring out what can sustain their parents’ attention, make them feel worried, etc.

- Do not respond to “noise”/learned helplessness/emotional manipulation with attention or emotional reactivity. This does not mean ignore, it means do not give those words/behaviors a response.

- It is irrelevant if self-defeating comments are genuine or not, you don’t give energy to them.

Avoid playing “armchair therapist”, you do not need to get to the bottom of every time your son is upset/angry/frustrated. § You can help your child build self-confidence through putting them in competent roles

- When you stop responding to noise/learned helplessness and emotional manipulation, your son may increase the frequency or severity of these behaviors, because they are not working like they used to for him. Things may have to initially get worse before his behavior starts to improve.

- Tapping into episodic memory is critical to helping kids feel successful and connecting their past successes to the present. The terminology used to build episodic memory is: “same but different”.

A time to oneself for reflection is an opportunity to “save face” and self-correct through giving space to calm down. A time to oneself for reflection is not a “time out”. It’s an opportunity to get to a calmer state of emotional regulation. The length of time of a time to oneself for reflection is his choice, not yours.

You suggest a time to oneself for reflection, do not demand it

WHY

- Kids with ADHD often feel ashamed about their words/behaviors, after the fact. This gives them a chance to redeem themselves through having a “second chance”.

- If they do a time to oneself for reflection and are still emotionally escalated, we tell them they can take some more time and come back when they’re ready to do a time to oneself for reflection. If they say they won’t do that, then you disengage and stop giving attention.

- time to oneself for reflection does not happen overnight, it may take months, or even longer for a time to oneself for reflection to happen. Some kids may not be able to do time to oneself for reflection until they’re teenagers. The important part is that you don’t stop trying. Emotional reactivity is one of the areas that does not go away in adulthood for many people with ADHD, which is why this is essential.

A time to oneself for reflection is Not

- A punishment or a “time out”. There is a place for consequences, that is addressed in another section.

- To be delivered with a negative/angry/punitive tone.

- Something you suggest during times when there is screaming, getting physical, etc. Suggest the time to oneself after things have deescalated a bit.

How I explain a “time to oneself for reflection” to kids

When our phone/computer isn’t working right, we turn it off and turn it back on to time to oneself it. We do this to quiet it down for a minute and then come back working again.

When you do a time to oneself for reflection, it’s a way for you to calm your brain down and handle things in a way that you’ll feel better about.

Let’s figure out how you want to do time to oneself for reflection. (Some will need to be told what to do, if they can’t figure out some time to oneself for reflection options on their own, particularly younger kids.)

Troubleshooting time to oneself for reflection

“I’m not doing a stupid time to oneself for reflection!”

This should be met with an acknowledgement and removal of attention. You can say:

“O.K. just let me know when your brain is calm.”

If they do a time to oneself and are still emotionally escalated, using an angry tone, etc. we can point out that it sounds like their brain isn’t calm yet and that maybe they need to take some more time for their brain to calm down.

Never get into a back and forth regarding whether a time to oneself is warranted or not, that is getting sucked into the argument rabbit hole.

Important things to keep in mind about time to oneself for reflection

- They do not need to be done in isolation.

- You should not talk while he’s calming down. You can make “small talk” if that will help, or he initiates. This is not a time for negotiating, talking about feelings, rehashing what happened, etc. Your job is to just be present.

- Physical affection is always fine during time to oneself if it’s helpful.

- Always offer 2-3 opportunities to do a time to oneself, before withdrawing attention if it’s not working.

time to oneself will almost never happen when very escalated/upset

Younger kids often need some sensory input/physical during a time to oneself (under blanket, you holding him without talking,

going outside for a walk around the block, etc.) Emphasize that a time to oneself is about “calming our brain down so we

can hear our Brain Coach again”, it is not a punishment

Middle school age time to oneself

time to oneself cannot happen when very escalated/upset.

Some middle school kids benefit from some sensory input during a time to oneself (under blanket, doing a physical activity, going outside for a bit, etc).

Emphasize that a time to oneself is about “calming our brain down so we can hear our Brain Coach again”, it is not a punishment.

Do not give any acknowledgement/attention to cursing/bad words used when he’s escalated.

High school age time to oneself

I tend to be more direct and not use the term “time to oneself”. Example: “The tone you’re using right now is not working for me.

I won’t be able to listen when you’re speaking this way. Find something to calm your brain down and we can discuss this when you’re ready.” I suggest not giving any attention to cursing/bad words used when he’s escalated.

- time to oneself is opportunities to use better self-regulation and toself-correct. They should be offered 3 times before you withdraw attention.

- There is not specific time frame a time to oneself should take, that depends on your child’s ability to get to a better state of self regulation.

- Time to one self is offered, there are no consequences for not doing a time to oneself.

- Always remember to use purposeful praise when your son does a time to oneself. This is essential.

- The ADHD brain tends to be concrete, focused on small/irrelevant details and can struggle with the abstract (concepts, themes, “the bigger picture”, etc.)

- Many younger kids tend to be “black or white” in their thought process. While this often improves with age, there are many adults with ADHD who still struggle significantly with this.

- Being clear, concise and concrete is way of using language that is best suited for the ADHD brain.

How not being clear, concise and concrete can affect kids with ADHD

- Trying to frame things in the positive is often abstract for kids with ADHD. While it sounds nice, it’s not what works best for the ADHD brain.

- How you communicate is essential. I’ve worked with many kids who quickly escalate because their parents are too verbose (not concise), feel the need to rehash the sequence of events (not concise), are not direct with them (not clear) or tend to use fluffy/abstract language (not concrete).

Why we should be clear and concise

- Many adults try to “sugarcoat” things or using language that is abstract.

Abstract: “Use kind words in our house.”

Clear, concise & concrete: “You do not curse or insult each other.”

- You help to facilitate success when we are clear, concise and concrete in our language because it provides clear parameters of behavioural expectations.

- Using “fluffy”, abstract language is never helpful, particularly for younger kids because it requires too much inferencing, a skill that is often lagging in kids with ADHD.

Examples of how it sounds

- When you go into the dentist’s office you shut your phone off and put it in your pocket.

- After you are done with Legos make sure that the basement matches the picture of what the basement is supposed to look like.

- When it is time to leave for your sister’s game you’re expected to get in the car when I tell you, without arguing. If you choseto do that, you chose to have your phone at the game

- At 6:00 I’m going to call you to set the table for dinner, make sure you are watching when the big hand moves into five minute warning time, so you are ready

Think

- Is there a way for me to use 80% less words than I was intending?

- How do I say this so it’s clear, concise and concrete?

- You can always rephrase things to be more clear, concise and concrete.

- The way you use language with your child is incredibly important.

- The ADHD brain is often concrete and sees things as “black or white”. Additionally, many kids with ADHD (particularly younger) are lagging in their inferencing skills, which is why abstract or “fluffy language” such as stating things in the positive is not helpful.

- Before you say something, remind yourself to use 80% less words and think about how you want to frame what you’re going to say so it’s clear, concise and concrete.

- Your son doesn’t need to agree with your decisions.

- You don’t need your son’s approval for your decisions.

- Going down the argument/reasoning/negotiation rabbit hole makes you look less confident in your parenting decisions. That doesn’t feel good to your son, when he sees that he can control you.

- Kids need to see their parents as capable and confident in order to feel emotionally safe.

The argument rabbit hole can be defined as:

- Parents getting pulled into an argument, directed by their child that often goes off on tangents that are unrelated to the original topic.

- A way for kids to obtain parents undivided attention.

- A way kids try to avoid non-preferred tasks or having demands placed on them.

- A very common pattern in families of kids with ADHD, that often lasts for years.

- Arguing is sometimes to often based in inflexibility and difficulty with perspective-taking.

- When you respond to arguing with discussion, you are reinforcing that arguing engages you and gets your undivided attention.

- When you try to make your son feel heard, through giving attention to the arguing, you are validating its effectiveness

The reasoning rabbit hole

- A common way parents try to deal with their child’s inflexibility. The problem is you cannot reason someone out of being inflexible.

- You can choose to not accommodate their inflexibility.

- I have regularly seen parents of kids with above average verbal ability get pulled into the reasoning rabbit hole

- A way parents undermine their own parental authority by trying to use logic to get their child to understand their perspective or reason for something.

- I have seen parents get pulled into the reasoning rabbit hole by utilizing certain parenting approaches that encourage *partnership parenting.

- Quite a few parents have shared with me that when taking their child to therapy, the sessions resulted in getting pulled into the reasoning or negotiation rabbit hole, because the therapist would treat their child like an adult.

Negotiation Rabbit Hole

- Getting pulled into the negotiation rabbit hole undermines your parental authority, and teaches your son that with enough effort, you can be worn down, so he gets what he wants.

- Kids with ADHD do best when things are concrete, and they know their parents are in charge. This provides a sense of emotional safety. You getting pulled into the negotiation rabbit hole can make your son feel less emotionally safe because you look less secure in your parenting decisions

WHAT TO DO

Avoiding the argument rabbit hole

- It takes two people to argue.

- You can make the conscious choice to disengage from an argument.

- This may escalate your son more, particularly when you start disengaging from getting pulled into arguments.

- If that happens, do not responding to his escalation with attention/emotional reactivity.

- If you say “No” to something he wants and he won’t drop it, you can let him know. “My answer is not going to change. I don’t want to ignore you however if you keep on asking me this over and over then I will ignore you until you choose to get your brain unstuck.”

- This is acknowledging you are not ignoring him, and it is using language of accountability.

- I find that fathers often get pulled into the argument rabbit hole much easier than mothers. This often becomes a battle of who’s going to have the last word, which is completely useless.

STORY

When I made the decision to stop getting pulled into the argument rabbit hole with my son, it escalated him. He would then resort to threats (emotional manipulation) and breaking things. I had to learn to respond with calmness.

The escalation from getting pulled into the argument rabbit hole stopped, however he continued to try to argue. My response would be to not say anything. I was not ignoring him. I would make eye contact with him, occasionally I might respond with “O.K.” to his threats but that was the extent of my answering him. His breaking things received no response

Avoiding the Negotiation rabbit hole

- You need to remain secure in standing by your decision. This may mean that your son is upset with you. He may resort to emotional manipulation as a result of being upset with you.

- When your son tries to present you with justification for his negotiation, acknowledge that you appreciate he was (nice to his sister, helped clean up from dinner, etc.)

- Create some “sound bites” to respond to negotiation: “I appreciate you offering to unload the dishwasher and it would mean a lot to me if you did that. My answer about computer time is going to be the same.”

- I have seen many kids who are highly skilled at successfully negotiating with their mothers because they do things that “softens up” their mothers such as acting babyish or being affectionate when they want something.

- When mothers find these behaviors endearing, it is much easier for kids to manipulate them to get what they want

Avoiding the reasoning rabbit hole

You cannot reason with inflexibility, so don’t try.

You do not need your son to agree with you. This will require you being O.K. with him being upset with your parenting decisions.

- When kids are articulate or skilled at making a compelling argument, I frequently see parents get pulled into the reasoning rabbit hole because they believe they can use intellect to reason with their son.

- You cannot reason with inflexibility, so stop trying.

Kids with ADHD become experts at leading their parents into the argument/reasoning/negotiation rabbit hole.

- They can be relentless in their persistence which often wears parents down.

- Kids become more sophisticated about pulling their parents into argument/reasoning/negotiation rabbit hole as they get older. I have seen this parent child dynamic last into young adulthood.

- Being firm in your parenting decisions can be difficult, especially when your son is used to getting what he wants.

- When you stop getting pulled into the argument/reasoning/negotiation rabbit hole it may escalate your son because you’re no longer responding in a way he’s used to. This will feel like a loss of control to him. It is important you stand your ground and be O.K. with him being upset with you.

- Think about if your son is able to manipulate you by acting “babyish” or affectionate when he wants something or wants to “soften you up”.

- If you are a two-parent home, it is very important you point out to each other when you see each other getting pulled into the argument/reasoning/negotiation rabbit hole.

- Remember, not getting pulled into these does not mean ignoring, it means not getting pulled in and speaking in soundbites (if necessary).

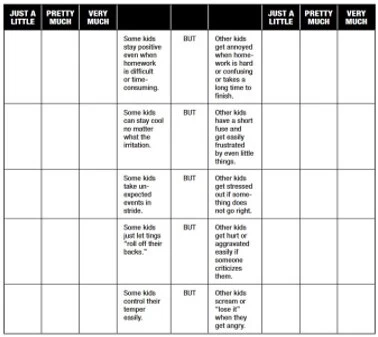

For each item in the chart, first decide whether the statement to the left or right of BUT describes your Child better. Then rate the degree to which that statement applies to your Child. The number of items for which you chose the right-hand statement is an indicator of how much improvement your Child may need in the skill overall. Your ratings indicate possible targets for skill building: Where you chose “pretty much” or “very much” for a left-hand statement, your Child is demonstrating good use of the skill in that particular domain. “Pretty much” or “very much” for right-hand statements indicates areas that may need the most work.